Concluding text adapted from “Decorative Arts in the Lower Shenandoah Valley” by Warren F. Hofstra and “Introduction” by Theodora Rezba from the Valley Pioneers and Those Who Continue catalogue, as well as “West of the Blue Ridge” promotional materials.

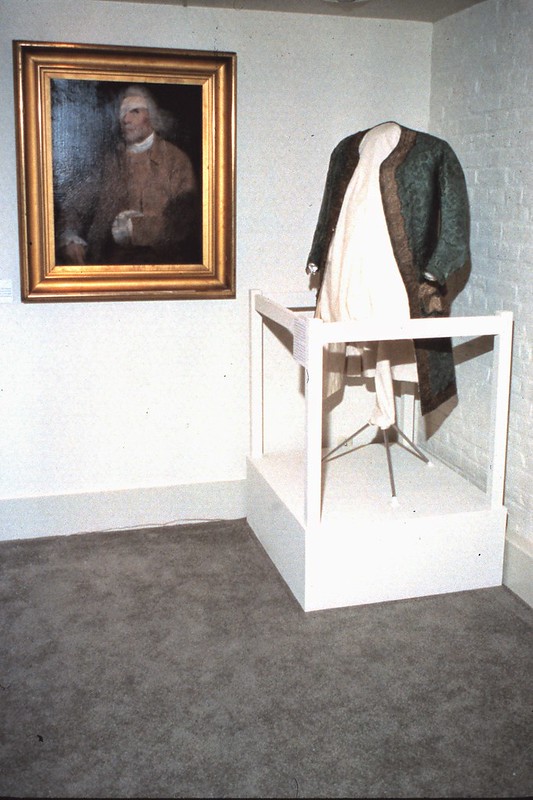

The social world of the Shenandoah Valley in the eighteenth century was something of an anomaly in Virginia. As we saw in the introduction to “West of the Blue Ridge,” German, Scotch-Irish, Dutch, Welsh, as well as English settlers came here, each bringing their own cultural heritage. The Lower Shenandoah Valley — present day counties of Frederick, Clarke, Warren, Shenandoah, and Page in Virginia, Berkeley and Jefferson in West Virginia, and Washington in Maryland — developed a unique artistic heritage through the interplay of these cultures.

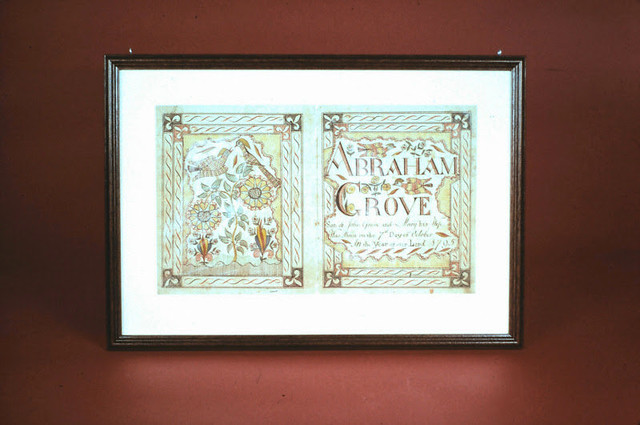

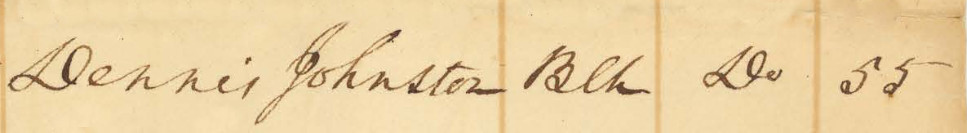

Even though the decorative elements employed on this Frederick County birth record are Germanic, the inscription is in English. The work of the so-called Virginia Record Book artist may represent a cultural assimilation of undetermined origin. The maker of this fraktur record is thought to be a Scotch-Irish schoolteacher who was closely allied to the German community in some way. Private Collection.

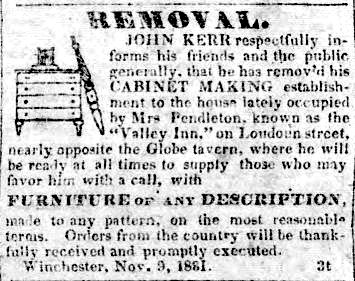

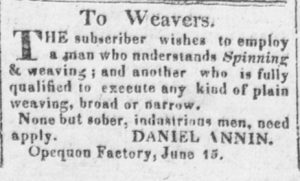

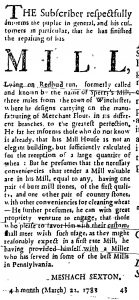

During the colonial period, local merchants kept a steady flow of goods streaming into the Valley from Philadelphia, giving the material culture a Pennsylvania slant. Artisans furthered this work, as many of them had received their training in Pennsylvania. Thus by the end of the eighteenth century much of the Lower Valley could boast of a highly pluralistic culture and an integrated goods and services economy generating a large volume of useful and decorative items reflecting the varied heritages. The distinctive Valley decorative art styles were forged in this vibrant atmosphere.

The next century told a different story as settlement fanned out far beyond the old Appalachian frontier. When Isaac Weld traveled Valley roads in 1796, he met “great numbers of people” searching “for lands conveniently situated for new settlements in the western country.” The quest for cheaper, larger quantities of land in less populated areas lured many local residents over the Appalachians.

When the National Road opened in 1818 to the northwest and then the mainline of the B&O railroad bypassed Winchester in 1827, migrants bypassed the Valley in their movement west. Wheat, at least for the decades before the American Civil War, remained a source of prosperity for Valley farmers, but the Valley had been bypassed as the commercial and cultural gateway west.

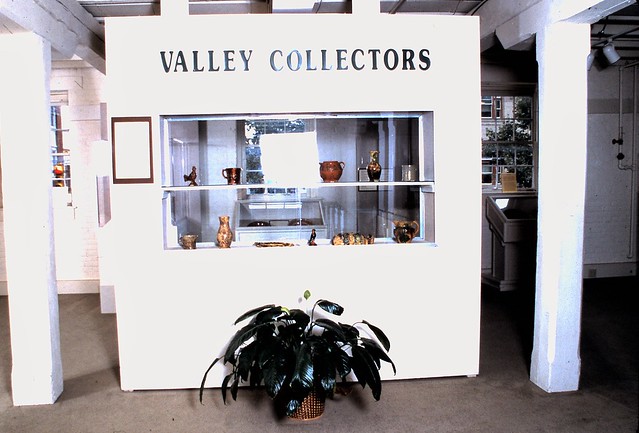

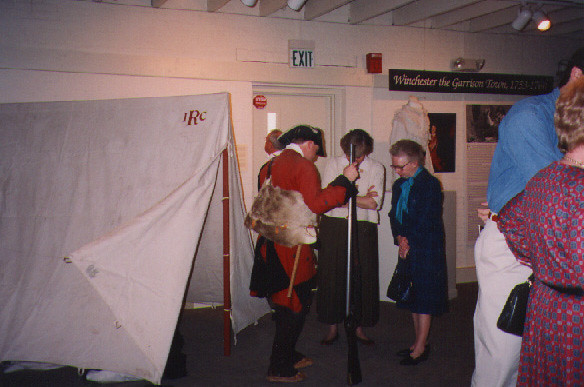

As with any museum exhibit, numerous people were involved in the creation of “West of the Blue Ridge.” However, as much time has elapsed since the exhibits were held, we may not be able to credit every person who worked on them thirty years ago. Kym S. Rice was the main exhibit curator, assisted by Dave and Jenny Powers, curators of the children’s exhibit. Theodora Rezba served as the Project Director, with other committee members consisting of Linden Fravel, Susan Galbraith, Mary Gardiner, Michael Gore, Ann Grogg, Warren Hofstra, Bobbi Jackson, Barbara Laidlaw, Teresa Lazazzera, Peggy McKee, Theresa Merkel, Dorothy Overcash, Eloise Strader, Anna Thomson, Sybil White, Joe Whitehorne, Gary VanMeter, and Patricia Zontine. Credited text contributors from outside the committee include H. E. Comstock, Virginia Miller, Timothy Hodges, Linda Crocker Simmons, Mary Bruce Glaize, and Tina Raburn.

The exhibit was made possible with contributions from the Virginia Foundation of the Humanities and Public Policy, the Hon. Harry F. Byrd, Jr., Nancy Larrick Crosby, the Durell Foundation, Elizabeth Engle, Dr. & Mrs. Hunter Gaunt, Michael Gore, Dr. & Mrs. Douglass O. Hill, Dr. & Mrs. Thomas Keenan, Dr. & Mrs. B. Franklin Lewis, Dorothy Overcash, Dr. & Mrs. David Powers, Dr. and Mrs. Benjamin Rezba, Thomas Scully, Eloise Strader, Dr. & Mrs. Larry Tolley, and Dr. & Mrs. David Zontine.

Thank you for joining us on this retrospective on “West of the Blue Ridge.” If you have an idea for a future multi-installment blog series, please drop us a note on social media or at phwinc.org@gmail.com.