One preservation issue had percolated quietly in the background of the 1970s and into the 1980s – the fate of the vacant old John Kerr School building at the corner of Cameron and Cork Streets. In 1974, the original John Kerr building closed its doors as a public school for the final time, leaving the building empty for nearly ten years. Speculation about the fate of the building started soon after it closed its doors. The fear was that the beloved old school would be demolished for a parking lot. (1)(2)

One preservation issue had percolated quietly in the background of the 1970s and into the 1980s – the fate of the vacant old John Kerr School building at the corner of Cameron and Cork Streets. In 1974, the original John Kerr building closed its doors as a public school for the final time, leaving the building empty for nearly ten years. Speculation about the fate of the building started soon after it closed its doors. The fear was that the beloved old school would be demolished for a parking lot. (1)(2)

The school was Winchester’s first endowed public educational facility. Local philanthropist and cabinetmaker John Kerr left a bequest of $7,000 to the City for the education of “poor white children” in 1870. His will was interpreted in such a way that the funds could be used to erect a public school building. Up to this point, the established public schools, although plentiful, were all rented spaces, often in the local churches or in private residences. With the Kerr bequest, which had subsequently grown to $10,000, and the City’s contribution of $6,000, Winchester’s first public school building was constructed from 1883-1884 in the Romanesque Revival style. The school originally consisted of ten rooms and accommodated about 300 to 500 students.

School enrollment boomed in the early 1900s with over 800 students by 1910, making the original building insufficient. The cornerstone for the addition to accommodate the surge in students was laid in 1908. In 1919, the overcrowding was further reduced by the temporary “chicken coops” located on the future grounds of the Handley High School. Virginia Avenue followed in 1931, and Quarles in 1955.

After serving students in Winchester for over ninety years, the old building was replaced with the new John Kerr Elementary School on Jefferson Street in 1972. It operated for two additional school years serving the the sixth grade during the construction of the Daniel Morgan Middle School before shutting its doors for the last time in 1974. With the school board having no further use for the building, the Council’s Municipal Building Committee recommended in 1975 to demolish Old John Kerr.

After serving students in Winchester for over ninety years, the old building was replaced with the new John Kerr Elementary School on Jefferson Street in 1972. It operated for two additional school years serving the the sixth grade during the construction of the Daniel Morgan Middle School before shutting its doors for the last time in 1974. With the school board having no further use for the building, the Council’s Municipal Building Committee recommended in 1975 to demolish Old John Kerr.

Knowing the significance of this building and fearing that a lack of ideas would lead to an untimely and unnecessary demolition for a parking lot, PHW allocated a portion of the grant funds received from the National Trust in 1975 to a feasibility study for the Old John Kerr, led by Arthur Zeigler. Several options for what could go into the building were suggested, including low income housing for the elderly, apartments, a community center, court facilities, or a museum. Although it was not a comprehensive survey by any means, it reaffirmed PHW’s concerns that this large building needed special attention and a specific purpose to be retained. Other ideas sprang up as well. The Winchester Host Lions Club made a separate proposal for shared nonprofit office and service space, while other ideas suggested uses as far ranging as a Bicentennial center, professional offices, nursing home, mental health facility, or Postal Service finance station.(3)

Applications to convert the building to a neighborhood center or a senior center were rejected in 1977. The old school began a slow decline into a vacant eyesore as the school board and the City worked through a potential snag by clearing the title to the three tracts of land comprising the school location and consolidating ownership of the John Kerr property. At the same time, the proposed uses for court facilities for the City and Frederick County fell through, as did the proposal to move postal services into the building. It seemed the time was finally right for the building to go up for sale and find a buyer. (4)

PHW pushed for the City to produce a new appraisal for the building with an eye toward purchasing the structure.(5) Several offers were submitted by the organization, but all were tabled or rejected. To ease some of the deterioration and buy the building more time, PHW volunteers helped secure the building against roof leaks and harsh winter weather and vandalism in 1979.(6) Bids opened again in 1980, and again PHW bid on the property.(7) Despite pessimistic forecasts of a lack of interest, a second bidder, Melco, Inc., also made a proposal for the property. Although both bids and plans were acceptable, both were rejected for undisclosed reasons.(8) (9) Speculation and worry on what would become of the Old John Kerr persisted.

Further information on Winchester’s schools can be found in Garland Quarles’ book, “Winchester, Virginia: Streets, Churches, Schools,” published by the Winchester-Frederick County Historical Society.

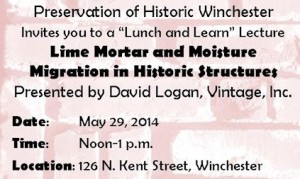

Finish National Preservation Month with this informative seminar. Preservation of Historic Winchester invites you to a the next “Lunch and Learn” Lecture on Lime Mortar and Moisture Migration in Historic Structures, presented by David Logan of Vintage, Inc. As always, this lecture is free and open to the general public.

Finish National Preservation Month with this informative seminar. Preservation of Historic Winchester invites you to a the next “Lunch and Learn” Lecture on Lime Mortar and Moisture Migration in Historic Structures, presented by David Logan of Vintage, Inc. As always, this lecture is free and open to the general public.