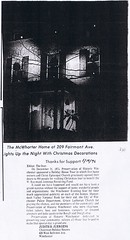

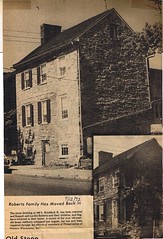

In 1978, PHW received its largest gift to date: the home of early founding member Lucille Lozier. “The Duchess,” who famously led PHW during the final year of the fight to save the Conrad House and laid the groundwork for the Historic District and Board of Architectural Review, bequeathed her home at 211 S. Washington St., some of her antiques, and a nucleus of funds to preserve and maintain the grounds to PHW.(1)(2)

In 1978, PHW received its largest gift to date: the home of early founding member Lucille Lozier. “The Duchess,” who famously led PHW during the final year of the fight to save the Conrad House and laid the groundwork for the Historic District and Board of Architectural Review, bequeathed her home at 211 S. Washington St., some of her antiques, and a nucleus of funds to preserve and maintain the grounds to PHW.(1)(2)

After discussion, the PHW board voted to accept the house and conduct feasibility studies to determine the best use of the house in accordance to the spirit of her will. The major consideration was to make the house self-sustaining, so that PHW could continue its work preserving other property with the Jennings Revolving Fund. The committee, consisting of Judy Juergans, Chuck Yerkes, Katie Rockwood, Lee Taylor, Jim Laidlaw, Eleanor White, and Betsy Helm were charged with this task.

In May, the committee returned with their findings. The house was in need of maintenance, so it was suggested some of the Lozier fund be put toward the repairs to the most pressing issues concerning the roof rafters and basement walls, and a decorator showcase could be held in the house as a fundraiser. However, the necessary structural work complicated the fundraising plan, and it appears the decorator showcase had to be cancelled.

Subsequently, the house was prepared for a single family residence rental property. It was anticipated that PHW would move its office into the Lozier House at a later point. However, the maintenance issues cost more and took longer to repair than anticipated. The house was not rented until 1980; this happily coincided with a lull in the Revolving Fund activity, which allowed PHW to operate as a landlord for a few years and to make incremental improvements to the property. By 1983, with the house substantially repaired, the grounds cleaned of dead trees and wild shrubbery, the Lozier maintenance fund depleted, and a number of significant properties becoming threatened in the downtown, the PHW board felt the pressure to get back into the Revolving Fund full time and end the landlord experiment. The Lozier House was sold to the tenants in 1983 with covenants similar to those placed on the Revolving Fund properties.

Subsequently, the house was prepared for a single family residence rental property. It was anticipated that PHW would move its office into the Lozier House at a later point. However, the maintenance issues cost more and took longer to repair than anticipated. The house was not rented until 1980; this happily coincided with a lull in the Revolving Fund activity, which allowed PHW to operate as a landlord for a few years and to make incremental improvements to the property. By 1983, with the house substantially repaired, the grounds cleaned of dead trees and wild shrubbery, the Lozier maintenance fund depleted, and a number of significant properties becoming threatened in the downtown, the PHW board felt the pressure to get back into the Revolving Fund full time and end the landlord experiment. The Lozier House was sold to the tenants in 1983 with covenants similar to those placed on the Revolving Fund properties.

Although PHW never utilized the Lozier House as office or special event space as Lucille Lozier envisioned, PHW members who knew her thought she would not wish the house to become a burden on the organization and would see the pragmatism in selling the house to others who could continue to care and treasure it. Proceeds from the sale were set aside as a nest egg to fund office staff salary and other Revolving Fund activities.

Information on the Lozier House from PHW’s unpublished minutes and Lozier House files. View other images of the Lozier House on Flickr.