We will return to our normal history posts next week, but for now, please enjoy some images of South Kent Street on Flickr.

We will return to our normal history posts next week, but for now, please enjoy some images of South Kent Street on Flickr.

We will return to our normal history posts next week, but for now, please enjoy some images of South Kent Street on Flickr.

We will return to our normal history posts next week, but for now, please enjoy some images of South Kent Street on Flickr.

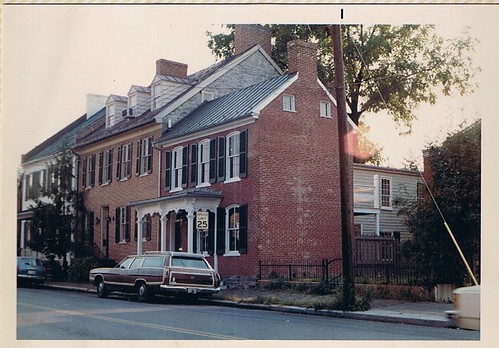

We take a little break from the downtown mall this week with a look at one of the more unique situations in PHW’s Revolving Fund history A row of four lots, encompassing 601, 603-605, 607, and 609 South Cameron Street, was purchased by the Jennings Revolving Fund in 1981. Like 215 South Loudoun last week, the three existing buildings were in poor condition, while a fourth had already been razed following a fire. This was the first, and to date only, time an empty lot was part of a Revolving Fund purchase. (1)

We take a little break from the downtown mall this week with a look at one of the more unique situations in PHW’s Revolving Fund history A row of four lots, encompassing 601, 603-605, 607, and 609 South Cameron Street, was purchased by the Jennings Revolving Fund in 1981. Like 215 South Loudoun last week, the three existing buildings were in poor condition, while a fourth had already been razed following a fire. This was the first, and to date only, time an empty lot was part of a Revolving Fund purchase. (1)

The properties were held for many years by two families. 601 and 603-605 S. Cameron were both built by James A. Fuller, a Winchester railroad engineer. 601 was constructed in 1846, and 603-605 in 1882 (though like 215 S. Loudoun, deed references indicate there may have been an earlier dwelling on the site which did not survive.) These properties remained in the Fuller family until 1946.

The house at 609 S. Cameron St., and the lot at 607, were both owned by the Funk family. 609 S. Cameron was constructed circa 1860 for Christopher Funk, a bricklayer. His son James N. W. Funk was an undertaker and proprietor of Funk and Ray Undertakers, located at 7 S. Market (Cameron) St. 607 and 609 S. Cameron remained in the Funk family until their purchase by PHW in 1981. (Note the Winchester Star cites the location of Funk and Ray Undertakers as 7 S. Loudoun St. It appears the error originated in PHW’s research and was passed on to the newspaper.)

The interesting story may be the house at 607 S. Cameron. The Funk-owned house here had been destroyed by fire in the 1920s. Although offered as a rare chance for new construction in the Historic District, the lot instead became a once in a lifetime chance to move a historic property from outside the district into its boundary. The house is recorded in PHW’s notes as originating from 901 S. Cameron St., approximately the juncture of Millwood Avenue/Gerrard Street and Cameron Street. Presumably this house was in danger of demolition for the strip mall now located at 101-113 Millwood Ave., which was constructed circa 1983. The May 1984 PHW newsletter notes this house was “laying on its side, under a black tarp” before the reconstruction process began.

The interesting story may be the house at 607 S. Cameron. The Funk-owned house here had been destroyed by fire in the 1920s. Although offered as a rare chance for new construction in the Historic District, the lot instead became a once in a lifetime chance to move a historic property from outside the district into its boundary. The house is recorded in PHW’s notes as originating from 901 S. Cameron St., approximately the juncture of Millwood Avenue/Gerrard Street and Cameron Street. Presumably this house was in danger of demolition for the strip mall now located at 101-113 Millwood Ave., which was constructed circa 1983. The May 1984 PHW newsletter notes this house was “laying on its side, under a black tarp” before the reconstruction process began.

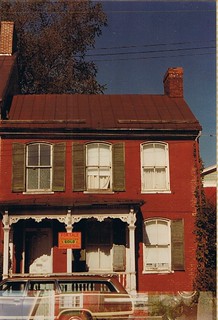

This Friday we bring you one of our favorite things: a photographic documentation of a building rehabilitation. The houses at the intersection of Cork and Loudoun Streets, just off the walking mall, had been in decline for some time, adding to the visual perception of the downtown as a dirty and unsafe place to be. PHW purchased the house at 215 South Loudoun Street in 1979. The building was in dilapidated condition, inside and out, and would require extensive work to make it inhabitable once more.

This Friday we bring you one of our favorite things: a photographic documentation of a building rehabilitation. The houses at the intersection of Cork and Loudoun Streets, just off the walking mall, had been in decline for some time, adding to the visual perception of the downtown as a dirty and unsafe place to be. PHW purchased the house at 215 South Loudoun Street in 1979. The building was in dilapidated condition, inside and out, and would require extensive work to make it inhabitable once more.

George and Vivian Smith stepped up to the challenge. Over the next two years, the Smiths worked on the home. The building was originally tentatively dated pre-1885; as work on the interior commenced, the existing moldings and mantels suggested a circa 1840-1850 timeframe. Later, the building received a facelift, adding Italianate features like the arched windows, doors, and front porch. A frame wing to the rear of the main brick house was apparently constructed over the site of an earlier structure. Archeological work during the rebuilding of the frame portion revealed the remains of a stone chimney, fragments of Canton ware, and an 1831 penny.

Deed research by PHW supports these archeological findings. The lot was purchased by John Lauck in 1821. Some sort of dwelling was likely in place by 1828 when it was purchased by William Blanchard. Language of the deed in 1852 when the property was sold to Edward Hoffman seem to indicate the brick house was not yet constructed. Tax records for 1881 indicate a jump in assessments, leading to speculation the Italianate improvements may have taken place that year.

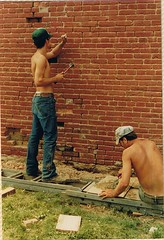

Work on 215 South Loudoun included repairing the existing porch and shutters, rebuilding and repointing the walls, jacking and leveling the frame extension and replacing the siding, and repairing and reglazing the existing windows. PHW placed special protective covenants on this property to specify all work during the repointing was to be done with hand tools to not damage the brick. Interior upgrades included new electrical, HVAC, plumbing, insulation, bathroom and kitchen facilities, as well as modifications to the interior stairs.

Work on 215 South Loudoun included repairing the existing porch and shutters, rebuilding and repointing the walls, jacking and leveling the frame extension and replacing the siding, and repairing and reglazing the existing windows. PHW placed special protective covenants on this property to specify all work during the repointing was to be done with hand tools to not damage the brick. Interior upgrades included new electrical, HVAC, plumbing, insulation, bathroom and kitchen facilities, as well as modifications to the interior stairs.

With so much work to be done, it will come as no surprise 215 South Loudoun was a tax credit project. It was granted a Winchester Historic Building plaque in 1982. Much like the Huntsberry Building, this property displayed a dramatic upswing in value post-rehabilitation. PHW sold the property for a little less than $23,000. In 1985, the Smiths’ asking price was $125,000. The building, just off the walking mall, was used by the Smiths for their business, but was returned to residential use by its current owners.

As we’ve seen over the past few weeks, PHW was becoming increasingly active in the future of the downtown. When the Huntsberry Building at 157 North Loudoun Street came on the radar as a Revolving Fund purchase, it was a perfect opportunity to demonstrate two proposed methods to keep downtowns vital against the encroachment of large shopping malls. One of these methods was to encourage more historic facade restorations, turning back some of the changes and restore a more authentic view of downtown. The Huntsberry Building would be a perfect and potentially dramatic example of this, as the facade had been covered in a cement and tile mixture in the 1940s or 1950s, obscuring the original Queen Anne details. It was also a perfect case to reintroduce upper story apartments to the downtown. The upper floors of the building had reportedly been vacant for twenty years in 1982. While in disrepair many Victorian-era architectural details were still intact on the upper stories, and the space could comfortably be divided into several apartments.(1)

As we’ve seen over the past few weeks, PHW was becoming increasingly active in the future of the downtown. When the Huntsberry Building at 157 North Loudoun Street came on the radar as a Revolving Fund purchase, it was a perfect opportunity to demonstrate two proposed methods to keep downtowns vital against the encroachment of large shopping malls. One of these methods was to encourage more historic facade restorations, turning back some of the changes and restore a more authentic view of downtown. The Huntsberry Building would be a perfect and potentially dramatic example of this, as the facade had been covered in a cement and tile mixture in the 1940s or 1950s, obscuring the original Queen Anne details. It was also a perfect case to reintroduce upper story apartments to the downtown. The upper floors of the building had reportedly been vacant for twenty years in 1982. While in disrepair many Victorian-era architectural details were still intact on the upper stories, and the space could comfortably be divided into several apartments.(1)

PHW began with the technical work to tackle the exterior restoration portion of this project, locating archival photos of the building and doing some hands on investigation to determine how the facade had once looked. One of the best guides was a circa 1886 photo, showing where windows had once been located and a different street level configuration of the storefront. John G. Lewis lent his architectural historian expertise to the building as well, confirming through trace evidence left in the building’s interior some of the puzzling exterior questions.

PHW secured a $30,000 loan from the National Trust, matched that amount with a local fund drive, and received a state grant of $14,000 to purchase the building and undertake the facade restoration project.(2) Work on the facade started in September of 1982, and almost immediately hit an unforeseen snag. During the tile removal, the brick wall was found to be very soft, possibly having been made from salmon bricks reused from another building previously on this site. The bricks and mortar were also theorized to have not been wetted sufficiently during construction, causing the mortar to fail much more rapidly than usual. The removal of the window frames, which were structural elements, further compromised the stability of the front facade. Even a careful approach to the cement and tile removal led to dangerous shifting of the wall and more damage to the bricks.

PHW secured a $30,000 loan from the National Trust, matched that amount with a local fund drive, and received a state grant of $14,000 to purchase the building and undertake the facade restoration project.(2) Work on the facade started in September of 1982, and almost immediately hit an unforeseen snag. During the tile removal, the brick wall was found to be very soft, possibly having been made from salmon bricks reused from another building previously on this site. The bricks and mortar were also theorized to have not been wetted sufficiently during construction, causing the mortar to fail much more rapidly than usual. The removal of the window frames, which were structural elements, further compromised the stability of the front facade. Even a careful approach to the cement and tile removal led to dangerous shifting of the wall and more damage to the bricks.

Fearing a collapse should this work proceed, a structural engineer was brought in. The first floor and foundation were found to be in good condition. During this time PHW members made the decision to rebuild in cinder block. In an ideal world, brick could have been custom ordered to replace that which had been damaged, but the committee felt there was a lack of expertise in historic mason techniques, so that the craftsmanship of this approach could not have duplicated the original facade satisfactorily. The cinder block wall would also reduce the weight on the first floor, and when plastered would still provide the intended historic flavor without bankrupting the organization.

Fearing a collapse should this work proceed, a structural engineer was brought in. The first floor and foundation were found to be in good condition. During this time PHW members made the decision to rebuild in cinder block. In an ideal world, brick could have been custom ordered to replace that which had been damaged, but the committee felt there was a lack of expertise in historic mason techniques, so that the craftsmanship of this approach could not have duplicated the original facade satisfactorily. The cinder block wall would also reduce the weight on the first floor, and when plastered would still provide the intended historic flavor without bankrupting the organization.

Although it was a potentially disastrous situation, the Huntsberry Building facade was rebuilt to much the way it appeared in the 1880s. The project was lauded as a successful experiment, with the apartments being rented soon after their completion in 1987.(3) The only downside was that the reconstruction of the failing front wall with cinder block precluded the project from realizing historic tax credit benefits. Although the owners who undertook the interior renovation put the building up for sale in 1992, the asking price was an indication of the project’s success and a turnaround in the downtown climate. PHW sold the building for $75,000. Ten years and one interior renovation later and the asking price became $300,000.(4)

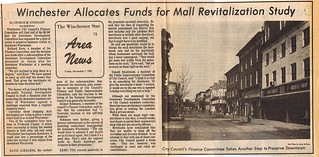

As mentioned last week, Winchester’s downtown was approaching a time of reckoning in 1980. Three mall developers were looking toward construction of a regional shopping mall in Winchester’s vicinity, and the anchor stores of the downtown – Leggett’s, Sears, and JC Penney’s – had all expressed interest in moving to this new location. Nearby cities that had not invested in their downtowns were experiencing a rapid decline in the older commercial districts, with vacant storefronts, vagrants and drug dealers, and arson and vandalism problems. Winchester hoped to steer away from that path of decline through proactive assessments and actions. (1)

As mentioned last week, Winchester’s downtown was approaching a time of reckoning in 1980. Three mall developers were looking toward construction of a regional shopping mall in Winchester’s vicinity, and the anchor stores of the downtown – Leggett’s, Sears, and JC Penney’s – had all expressed interest in moving to this new location. Nearby cities that had not invested in their downtowns were experiencing a rapid decline in the older commercial districts, with vacant storefronts, vagrants and drug dealers, and arson and vandalism problems. Winchester hoped to steer away from that path of decline through proactive assessments and actions. (1)

The special tax district that was put in place for the construction costs of the pedestrian mall was due to expire in 1983. Thoughts turned almost immediately to extending that tax and collectively using those funds to promote the downtown. More controversially, the tax could be expanded into an adjacent secondary district comprised of Piccadilly, Boscawen, Cameron, Braddock and Cork Streets. Proponents of this idea cited the tax would average about $500, or about the cost of a full page advertisement in the Winchester Star in 1980.

David Juergens, co-chair of the Downtown Development Committee studying this conundrum, laid out his thoughts on how an older downtown could adapt some of the ideas of the regional mall strategy. The pedestrian mall would have to become event and entertainment oriented, with attractions other than just shopping. A downtown administrator would be hired to coordinate among the merchants and paid for through the special assessment district and dues to the Retail Merchants Association. This was a similar strategy used by the shopping malls to keep a cohesive branding between the multiple stores. Vacant upper floors would be targeted to be filled and maximize the square footage of the downtown buildings. And as is fitting, he echoed the sentiments of architecture lovers everywhere: “We want people to come downtown where the architecture is real and the design honest.”

In November 1980, the National Development Council was hired to lay a financial plan for the downtown to compete against the expected regional mall. The other ideas of special assessment areas and a downtown manager to coordinate between all the merchants like the regional mall model were also met favorably. Efforts had previously been made to keep “alcoholics and slovenly dressed” away from the downtown via a dress code, but that law had been challenged and ruled unconstitutional. The other option was to turn the pedestrian mall into a private street, so that private security officers could be hired to patrol the area. (2) (3)

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of the plan was keeping and expanding the special tax district. It was a unique idea and is reportedly the only such district in Virginia. Expanding the assessment into a secondary district caused grumbles, because most of the focus of the downtown goes into the Loudoun Street corridor, then as now. Businesses in the secondary area countered that they could use the money from that tax to individually promote themselves, or that the burden of the tax would end up raising the rents on their spaces to the point where they would need to leave the downtown. (4) Officials, including Katie Rockwood of PHW, spoke in favor of the tax supporting the commercial downtown. From PHW’s perspective, a strong downtown helped to fuel our own Revolving Fund efforts. Although most of those properties are residential, the 30 properties that had passed through the Revolving Fund at that time were cited as spurring $1.6 million in investments. Those properties could not have been so successful in an economically depressed downtown climate. (5)

Irvin Shendow responded with a lengthy open forum piece as well, citing some of the positive changes that had started to take place with the construction of the pedestrian mall. Restaurants had moved downtown, store vacancies declined between 1974 and 1980, and renovations of buildings were on the upswing after 1975. He also noted that although a new regional shopping center might be a tempting move, rents there are almost always higher than in a downtown. He cited an average of $12 to $15 per square foot of space in a mall, compared to $2 to $4 per square foot in the downtown. Add in the regional mall fees, often three to five times the fees paid by the downtown merchants, and he doubted a bump up in rents from the downtown tax would kill the downtown’s “competitive pricing edge.” (6)

Irvin Shendow responded with a lengthy open forum piece as well, citing some of the positive changes that had started to take place with the construction of the pedestrian mall. Restaurants had moved downtown, store vacancies declined between 1974 and 1980, and renovations of buildings were on the upswing after 1975. He also noted that although a new regional shopping center might be a tempting move, rents there are almost always higher than in a downtown. He cited an average of $12 to $15 per square foot of space in a mall, compared to $2 to $4 per square foot in the downtown. Add in the regional mall fees, often three to five times the fees paid by the downtown merchants, and he doubted a bump up in rents from the downtown tax would kill the downtown’s “competitive pricing edge.” (6)

At PHW’s Annual Meeting in 1981, Porter Briggs spoke on the future of Winchester’s downtown. Although he warned the shopping mall was inevitable and the downtown would change, the two could coexist. The challenge would be to keep the downtown vital during this transitional process.(7) In the long run, his prediction has been proven correct – but it did take a long time to get there. Check in next week for a look at PHW’s direct contribution to the downtown mall with a facade restoration project at the Huntsberry Building!

The concern over the future for downtown commercial districts was not limited to Winchester. The National Trust for Historic Preservation saw and studied this need to stabilize downtowns against unprecedented pressures. The most common factor cited by the National Trust for the decline of downtowns across the country included the rise of new commercial construction in the form of strip malls. The Trust cites an increase in retail space from 4 square feet to 38 square feet per capita between 1960 and 2000, an increase which could not be supported by consumer spending. Instead of expanding the number of commercial enterprises, businesses were more likely to migrate to these newly constructed spaces.

The concern over the future for downtown commercial districts was not limited to Winchester. The National Trust for Historic Preservation saw and studied this need to stabilize downtowns against unprecedented pressures. The most common factor cited by the National Trust for the decline of downtowns across the country included the rise of new commercial construction in the form of strip malls. The Trust cites an increase in retail space from 4 square feet to 38 square feet per capita between 1960 and 2000, an increase which could not be supported by consumer spending. Instead of expanding the number of commercial enterprises, businesses were more likely to migrate to these newly constructed spaces.

Other factors the Trust cited that may not be quite so obvious at first glance stemmed from changes in land use. Zoning regulations fundamentally changed the way towns grew. In the past, small businesses and homes could coexist side by side, with neighborhood stores serving a few blocks as the need arose. Even larger businesses could be just a short walk from residences, or cause a new residential neighborhood to spring up around it to provide housing for the workers. With zoning regulations more firmly separating the notion of residential and commercial districts, main streets with their “mixed use” character were out of date. In general, upper story living spaces were erased from downtowns.

The last factor is the “car culture” that rose in the wake of increased American prosperity, fueled by the interstate highway systems making travel by car faster and more efficient. Downtowns were ill-equipped to adapt to cars, leading to unprecedented numbers of tear downs for parking lots and gas stations. Highways often bypassed towns completely, isolating the older commercial districts and leading to the boom of commercial construction along these new travel corridors.

The pedestrian mall changes to Winchester in the 1970s was an early way the town tried to adapt to the changing retail market. By 1981, it was clear this was an insufficient band aid to a deeper, endemic problem. The area’s first major competition to the downtown was looming as the Apple Blossom Mall project was becoming a reality — and taking key stores out of downtown. Something had to happen to prevent a complete collapse of the downtown.

PHW became aware of the test programs spearheaded by the National Trust taking place in select cities in the late 1970s. When the test program was preparing to launch in Virginia, PHW collaborated with the City in the attempt to bring the Main Street Program to Winchester. We succeeded. In 1985, National Trust experts descended upon Winchester to help set up what we know of today as the Old Town Development Board. But even before the program launched, Winchester and PHW were experimenting to keep activity in Old Town, which we will cover in more detail in the coming weeks.

Learn more about the National Main Street Center and the Four Point Approach to preserving downtowns at their website, www.preservationnation.org/main-street/

By 1980, the downtown mall was facing a crisis as more key stores were lured away from Loudoun Street for strip malls on the fringes of town. Downtown entertainment and cultural activities were few and far between. Serious, comprehensive revitalization plans and a vision for the mall’s future were necessary in order to prevent a complete catastrophe.(1) (2) PHW was prepared to help the budding downtown revitalization efforts.(3) One way to accomplish that in a way that meshed well with PHW’s mission was through revisiting the architectural walking tour.

By 1980, the downtown mall was facing a crisis as more key stores were lured away from Loudoun Street for strip malls on the fringes of town. Downtown entertainment and cultural activities were few and far between. Serious, comprehensive revitalization plans and a vision for the mall’s future were necessary in order to prevent a complete catastrophe.(1) (2) PHW was prepared to help the budding downtown revitalization efforts.(3) One way to accomplish that in a way that meshed well with PHW’s mission was through revisiting the architectural walking tour.

PHW had first made a foray into the world of self-guided architectural walking tours as a promotion of Winchester and its architecture in the 1970s, culminating in 1976 with a tour booklet written by Katie Rockwood and sponsored by several local banks. The tour itself had been praised highly by the National Trust for historic preservation in 1976 as being informative and easy to understand. The best part in the eyes of the National Trust consultant was the architectural style guide and glossary with its simple but informative illustrations and text. PHW updated the tour text, revised some photographs, reached out to more downtown businesses as sponsors, and reprinted the booklet in 1981. Although now out of print and the tour text and photos are once again out of date, the highly praised introductory text, architectural style guide, and glossary have been digitized and added to PHW’s growing digital library as a supplement to the more current walking tours. View the 1976 architectural walking tour introduction and glossary.

In addition to the self-guided format of the booklet, PHW volunteers also led guided walking tours in the fall of 1984 and 1985 based on Katie Rockwood’s text.(4) Tours were also adapted for elementary age students and parents through Winchester Public Schools, reportedly drawing in 100 participants for one iteration. (5) PHW continues to stay involved with the walking tour scene, have helped produce the 250 Years of History and Architecture and Civil War self-guided and guided tours in the 1990s, and continues to host one-time tour events like the Italianate guided tour and the recent church tour.

In addition to the self-guided format of the booklet, PHW volunteers also led guided walking tours in the fall of 1984 and 1985 based on Katie Rockwood’s text.(4) Tours were also adapted for elementary age students and parents through Winchester Public Schools, reportedly drawing in 100 participants for one iteration. (5) PHW continues to stay involved with the walking tour scene, have helped produce the 250 Years of History and Architecture and Civil War self-guided and guided tours in the 1990s, and continues to host one-time tour events like the Italianate guided tour and the recent church tour.

Just producing a walking tour by itself is no guarantee of getting more people to come downtown or boost tourism, but walking tours, particularly when combined with pithy historical facts, is one way to start generating “buzz” about buildings that might otherwise be overlooked.

Have you been on a walking tour of Winchester lately? Check out the selection of guided and self-guided tours available at the Visitors Center. Is there a tour idea you’d like to see produced in the future? Let us know!

|

| From Loudoun Street, circa 1980 |

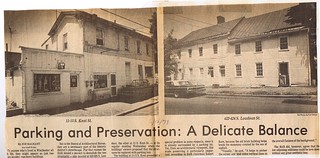

In 1979, founding PHW member and historian Ben Belchic passed away and left a bequest to PHW.(1) Knowing his interest in documentation of Winchester’s history, and his propensity to push others to do that research, the bequest was earmarked for a special project for the Revolving Fund. The opportunity to use that bequest came when a significant log duplex on South Loudoun Street was proposed for demolition as a parking lot.

In 1979, founding PHW member and historian Ben Belchic passed away and left a bequest to PHW.(1) Knowing his interest in documentation of Winchester’s history, and his propensity to push others to do that research, the bequest was earmarked for a special project for the Revolving Fund. The opportunity to use that bequest came when a significant log duplex on South Loudoun Street was proposed for demolition as a parking lot.

The Jennings Revolving Fund acquired the property at 422-424 South Loudoun Street to prevent its loss. It was apparent this property was a bit different from others that had passed through the fund. Although incredibly dilapidated after its use as apartments, the house held an architectural secret in its framing.

The older building at 424 S. Loudoun St., constructed by Godfrey Miller circa 1768-1777 (with remains of a smaller stone building circa 1750 incorporated into the log expansion) displayed an unusual construction technique for Winchester. The building was constructed with vertical corner post and plank, or post-and-plank log construction, a technique commonly associated with German settlers yet rarely observed in this area. Other buildings in Winchester may have this construction technique, though this is the only example documented in town. It is a feature impossible to observe from an exterior architectural survey because it lies solely within the bones of the house. In addition, tradition states that logs from Fort Loudoun were repurposed in the construction of this (and other) homes around town.

Because of this unique construction technique and the fortuitous bequest from Ben Belchic, Douglass Reed was hired to lend his expertise in log construction to the documentation of the Godfrey Miller House. A short section was included on the younger (circa 1800) half of the duplex, the Peter Miller House at 422 S. Loudoun St., as well. This report is now available online to researchers: Godfrey and Peter Miller House Report.

The Peter Miller House was purchased from the Revolving Fund by John G. Lewis.(2) That name may be very familiar to those who have been following along with the Friday posts. As an architectural historian, John Lewis documented the work he did and the history of his side of the house. This report is now also available to researchers online: Peter Miller House Report.

These two homes have come a long way since their time as apartments in the mid-twentieth century. To see more of the evolution of the Godfrey and Peter Miller House, visit the Revolving Fund Flickr album.

As we saw last week, the future of the Old John Kerr School remained in limbo after bids from PHW and Melco were rejected by the City Council. The disposition of the Old John Kerr building became perhaps the most troubling stumbling block to the preservation of the building. Everyone seemed to agree that the building should be saved, was of vital importance to our history, and the best use of the site was not as a parking lot. The only way to enact the preservation was for the building to be sold, and yet bids or plans after six years had swayed the City to part with the building. PHW continued to champion for Old John Kerr, hoping to find another outside entity that could purchase and rehabilitate the old school.

As we saw last week, the future of the Old John Kerr School remained in limbo after bids from PHW and Melco were rejected by the City Council. The disposition of the Old John Kerr building became perhaps the most troubling stumbling block to the preservation of the building. Everyone seemed to agree that the building should be saved, was of vital importance to our history, and the best use of the site was not as a parking lot. The only way to enact the preservation was for the building to be sold, and yet bids or plans after six years had swayed the City to part with the building. PHW continued to champion for Old John Kerr, hoping to find another outside entity that could purchase and rehabilitate the old school.

In 1981, a Boston developer was given the green light to redevelop the school into apartments, but again, the deal fell through when federal assistance did not materialize.(1) (2) It was not until 1982 that Shenandoah University (then Shenandoah College and Conservatory of Music) proposed to use the building for nursing and music branch, as well as a community arts center. Despite all the previous setbacks with the various offers on the building, optimism about this deal was high. SU President Jim Davis had done his homework, approached the right people well in advance, and made this offer as painless – and as tempting – to the City as possible.(3) (4)

Like the Conrad House, the affection held for this building brought forth an outpouring of support from the community – this time financial in nature. PHW was thrilled by the prospect of the college tackling the renovation and donated $10,000 to the project in 1982.(5) (6) (7) To help meet the pledge amount, PHW produced “Save John Kerr – It’s Elementary” bumper stickers for every $10 donation. Many other entities also contributed to the project, ensuring the Old John Kerr would not run out of resources before the building could be polished and furnished. In conjunction with the financial support, Winchester Star editorials and retrospectives of the school kept the issue in the limelight as the building approached its centennial year in 1983, reopening at last as another educational center for the community.

Although prospects for the school had looked bleak through much of the 1970s and early 1980s, the persistence and commitment of Winchester’s citizens to retaining their beloved school paid off. Shenandoah University continues to operate the building as the Shenandoah Conservatory Arts Academy, offering children instruction in dance, music, theater, art, and fitness, continuing the legacy of the philanthropist John Kerr and his vision for education the children of Winchester.

One preservation issue had percolated quietly in the background of the 1970s and into the 1980s – the fate of the vacant old John Kerr School building at the corner of Cameron and Cork Streets. In 1974, the original John Kerr building closed its doors as a public school for the final time, leaving the building empty for nearly ten years. Speculation about the fate of the building started soon after it closed its doors. The fear was that the beloved old school would be demolished for a parking lot. (1)(2)

One preservation issue had percolated quietly in the background of the 1970s and into the 1980s – the fate of the vacant old John Kerr School building at the corner of Cameron and Cork Streets. In 1974, the original John Kerr building closed its doors as a public school for the final time, leaving the building empty for nearly ten years. Speculation about the fate of the building started soon after it closed its doors. The fear was that the beloved old school would be demolished for a parking lot. (1)(2)

The school was Winchester’s first endowed public educational facility. Local philanthropist and cabinetmaker John Kerr left a bequest of $7,000 to the City for the education of “poor white children” in 1870. His will was interpreted in such a way that the funds could be used to erect a public school building. Up to this point, the established public schools, although plentiful, were all rented spaces, often in the local churches or in private residences. With the Kerr bequest, which had subsequently grown to $10,000, and the City’s contribution of $6,000, Winchester’s first public school building was constructed from 1883-1884 in the Romanesque Revival style. The school originally consisted of ten rooms and accommodated about 300 to 500 students.

School enrollment boomed in the early 1900s with over 800 students by 1910, making the original building insufficient. The cornerstone for the addition to accommodate the surge in students was laid in 1908. In 1919, the overcrowding was further reduced by the temporary “chicken coops” located on the future grounds of the Handley High School. Virginia Avenue followed in 1931, and Quarles in 1955.

After serving students in Winchester for over ninety years, the old building was replaced with the new John Kerr Elementary School on Jefferson Street in 1972. It operated for two additional school years serving the the sixth grade during the construction of the Daniel Morgan Middle School before shutting its doors for the last time in 1974. With the school board having no further use for the building, the Council’s Municipal Building Committee recommended in 1975 to demolish Old John Kerr.

After serving students in Winchester for over ninety years, the old building was replaced with the new John Kerr Elementary School on Jefferson Street in 1972. It operated for two additional school years serving the the sixth grade during the construction of the Daniel Morgan Middle School before shutting its doors for the last time in 1974. With the school board having no further use for the building, the Council’s Municipal Building Committee recommended in 1975 to demolish Old John Kerr.

Knowing the significance of this building and fearing that a lack of ideas would lead to an untimely and unnecessary demolition for a parking lot, PHW allocated a portion of the grant funds received from the National Trust in 1975 to a feasibility study for the Old John Kerr, led by Arthur Zeigler. Several options for what could go into the building were suggested, including low income housing for the elderly, apartments, a community center, court facilities, or a museum. Although it was not a comprehensive survey by any means, it reaffirmed PHW’s concerns that this large building needed special attention and a specific purpose to be retained. Other ideas sprang up as well. The Winchester Host Lions Club made a separate proposal for shared nonprofit office and service space, while other ideas suggested uses as far ranging as a Bicentennial center, professional offices, nursing home, mental health facility, or Postal Service finance station.(3)

Applications to convert the building to a neighborhood center or a senior center were rejected in 1977. The old school began a slow decline into a vacant eyesore as the school board and the City worked through a potential snag by clearing the title to the three tracts of land comprising the school location and consolidating ownership of the John Kerr property. At the same time, the proposed uses for court facilities for the City and Frederick County fell through, as did the proposal to move postal services into the building. It seemed the time was finally right for the building to go up for sale and find a buyer. (4)

PHW pushed for the City to produce a new appraisal for the building with an eye toward purchasing the structure.(5) Several offers were submitted by the organization, but all were tabled or rejected. To ease some of the deterioration and buy the building more time, PHW volunteers helped secure the building against roof leaks and harsh winter weather and vandalism in 1979.(6) Bids opened again in 1980, and again PHW bid on the property.(7) Despite pessimistic forecasts of a lack of interest, a second bidder, Melco, Inc., also made a proposal for the property. Although both bids and plans were acceptable, both were rejected for undisclosed reasons.(8) (9) Speculation and worry on what would become of the Old John Kerr persisted.

Further information on Winchester’s schools can be found in Garland Quarles’ book, “Winchester, Virginia: Streets, Churches, Schools,” published by the Winchester-Frederick County Historical Society.