The music for this installment is “Let Your Hammer Ring.”

Information for this installment is derived from H.E. Comstock’s introduction to Furniture in “Valley Pioneer Artists and Those Who Continue” and the “West of the Blue Ridge” exhibit texts.

The Shenandoah Valley was isolated from most commercial sites in its early history. Valley residents of more abundant means brought furniture from larger cities such as Alexandria, Baltimore, and Philadelphia prior to 1785. The early furniture styles of more modest residents reflect indigenous as well as outside influences.

Valley furniture presents definite influences of the English, German, Scotch-Irish, and Swiss immigration to the area. The forms show a spectrum of accents from fairly sophisticated carved pediments and ball and claw feet to elaborate wood or sulphur inlays. Fluted and stop-fluted quarter columns are commonly found, as well as furniture that is considered folk art due to its unique construction and decoration. The molding styles of local furniture is often replicated in the architectural moldings of Valley homes.

As is common in other areas, there are also many primitive or plain objects to be found. The painted dower chests of Shenandoah and Page counties in Virginia and close by Maryland counties are highly sought by collectors and museums nationwide. The elusive nature of the objects ranks them among the most desirable folk art furniture in America. Their primitive, naive, painted motifs render them the epitome of American folk art.

Primary woods for furniture construction, in order of occurrence, were pine, walnut, cherry, poplar, chestnut, and maple. It was not until the very late eighteenth century that mahogany began to be imported for furniture use. Secondary woods used, in order of occurrence, were pine, poplar, walnut, chestnut, and oak.

While the furniture of the Valley is often stylistically similar to other areas, it does occasionally exhibit evidences of local individuality. Distinguishing features included arced stop-fluting of the quarter columns, and precisely and elaborately carved capitals of quarter columns. Case pieces show well-executed carvings of shells and foliage on their pediments. These case pieces often exhibit so-called dust boards between drawers. Often a piece exhibits the bottom boards of drawers arranged from front to back. The back-boards of case pieces are sometimes arranged from side to side. Similar arrangements of these boards are commonly found in English furniture.

In the past it has been considerably difficult to make definitive attributions concerning the products of Shenandoah Valley cabinetmakers. The loss of records in courthouse fires and the fact that very few craftsmen signed their work makes such attribution less than easy. Our best evidence comes through repetitive occurrences of furniture styles and consistent craftsmanship, sometimes aided by impeccable family histories and various documentation.

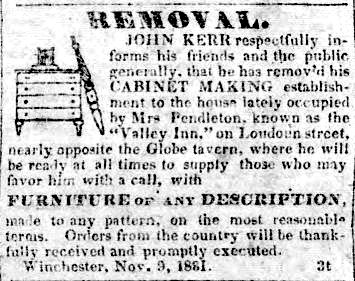

As in other early American communities, many of the local cabinetmakers were either itinerant or short-lived business enterprises. Among craftsmen known are David Campbell, Joseph Culbertson, Patrick Curry, Christopher Frye, J.S. Hendricks, John Kerr, William King, George Keyes, James L. Martin, Joshua Newbrough, George Newsom, John Shearer, and Edward Slaytor.

Johannes Spitler is perhaps the greatest example of decorative arts married to furniture originating in the Shenandoah Valley. It is not known if Spitler was responsible for his own casework, although some evidence suggests that possibility. Spitler’s painted designs of geometric patterns and compass work are usually found in the colors of red, yellow, white, blue, and black. He usually sealed the pores of the casewood and created a painting ground by applying an orange-red primer. Spitler’s decorations exist in a number of variations; a sizeable collection of his work has been found and pieces can be viewed online at the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts and the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley.

The “folksy” carvings, inlay patterns, and mixture of period designs on the same piece have always been one hallmark of local furniture. The citizens of the area have always been blessed by their geographical location. Of their many other blessings, one is the wonderful heritage of Shenandoah Valley furniture.

If you found this brief dive into local furniture intriguing, you may also wish to read A Southern Backcounty Mystery: Uncovering the Identity of a Northern Shenandoah Valley Cabinetmaking Shop by Patricia Long-Jarvis for a more in-depth look at the partnership of Joshua Newbrough and Job Smith Hendricks, as well as other local cabinetmakers active in the period of “West of the Blue Ridge.”

Our final installment concluding West of the Blue Ridge will be posted on June 3.