The music for this installment is “Wondrous Love.”

This installment is adapted primarily from “Pottery” by H.E. Comstock in the “Valley Pioneers and Those Who Continue” exhibit catalogue. Most scholarship on Valley pottery stems from Comstock’s work, which can be found in the “Encyclopedia of American Folk Art” edited by Gerard C. Wertkin, as well as “The Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region.”

Potters began migrating to the Shenandoah Valley as early as the 1760s. The constantly increasing population of an agrarian society and their subsequent need for food preservation made pottery production a prime industry. The abundance of native clays, clear and workable in their natural state, facilitated the growth of the industry. Between the years of 1760 and 1900, more than two hundred potters were associated with Valley pottery production.

With few exceptions, two types of pottery were produced in the Shenandoah Valley: earthenware and stoneware. Earthenware, which can be distinguished by its maroon-brown color and brittle nature from its low firing temperatures, was abundantly produced in the earlier years. Earthenware is naturally porous, so pieces were glazed with lead oxide to provide waterproofing. The lead glazes typically produced colors of green and brown through the addition of copper, manganese, and iron. Nearly every type of pottery that was made in the Valley was produced in earthenware at some point.

Stoneware, a harder and denser pottery with a greyish pebbled surface, was produced throughout the Valley, especially after 1840. Stoneware is nonporous and more resistant to breakage due to the clay being fired at higher temperatures, leading to stone-like qualities. The salt glaze commonly found on stoneware was produced by throwing table salt into the very hot kiln. Salt glaze can range from clear through brown, blue, or even purple, resulting in a finish similar to an orange peel. For the most part stoneware exists as crocks, jugs, pitchers, canning jars, pans, bottles, cuspidors, and chambers.

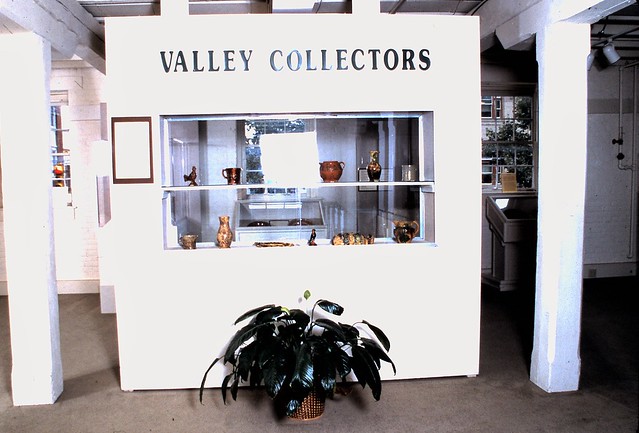

John George Weis is considered one of the first and most influential potters to settle in the Shenandoah Valley. Much like firearms of the frontier developing artisans of renown and schools of production, Weis is considered the founder of the “Hagerstown School” of pottery. More history and background information on other early potters in the Valley can be found at Shenandoah Pottery, but two families in particular were the focus of the artifacts on exhibit at the Kurtz Cultural Center.

By the end of the eighteenth century at least three potters worked in Newtown (Stephens City) making utilitarian redware or earthenware, mostly for the local market. It is believed Anthony Pitman knew Weis or was exposed to his pottery techniques in Germany and subsequently brought the Hagerstown school of pottery to Newtown (Life of a Potter, Andrew Pitman, p. 16). Andrew and John Pitman, Anthony’s sons, are believed to have learned their trade from their father.

“The earliest known reference to Pitman’s trade is a record of his purchase of ‘red lead’ (used for pottery glazes) from Winchester drug store owner, John Miller, in 1805.” Although he is known to have been an important and prolific potter for the area, little written documentary records remain, and it appears his work never traveled far beyond Winchester and Newtown. Fortunately, the Andrew Pitman house at 5415 Main Street in Stephens City was the subject of an in-depth archeological investigation, and more information on the artifacts of the pottery trade found there and the context surrounding the site can be found through the Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

“The commonest cups and saucers sold then for one dollar per set, and a great many persons used the earthen ware porringers and mugs manufactured at Newtown.” — William Greenway Russell

The Bell family of potters, known not only locally but nationwide, are more responsible for the renown of the Valley’s pottery tradition than any other group. This family started its pottery production in the late 1700s with the work of Peter Bell in Hagerstown, Maryland. Bell’s three sons, John, Samuel, and Solomon, worked in Hagerstown, Winchester, and Strasburg, as well as locations in Pennsylvania.

John Bell (1800-1880) worked with his father, Peter, until 1824, when Peter moved to Winchester. John rented his father’s old shop in Hagerstown for himself for a year, then he moved to Winchester and worked with his father for three years. Thereafter, he moved to Chambersburg, Pa., where potter Jacob Heart provided him experience with English ceramic-molding techniques. He was one of the first American potters to use tin in his glazes, drawing from the pottery of Delft, Holland. The outstanding quality of his work rates him at the very top of American potters of this period, owing to his combination of German and English techniques to form a uniquely Valley form. John Bell may be the most widely known of the Bell family potters, especially for his ornamental pottery like the whimsical lion in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Samuel Bell (1811-1890) learned his craft from his father in Winchester. He moved to Strasburg in 1842, and around 1845, he acquired the old Miller Pottery from his father-in-law. Stylistically, his work is similar to his father’s, along with adapting the techniques and forms used by his brother John. His clientele and his production methods compelled him to produce mostly utilitarian ware, yet his accomplishments as a potter were excellent, particularly in his brushwork. Marked pottery from Samuel’s Winchester era is considered some of the finest and most sought-after pieces of Shenandoah Valley pottery.

Solomon Bell (1817-1882) also learned his craft in Winchester with his father and brother Samuel. He occasionally worked with his brother John in Chambersburg before joining his brother Samuel in Strasburg around 1844 in their family pottery business. He was responsible for the first molded ware produced in Strasburg and produced colored pieces that were distinctive enough to inspire the moniker “Strasburg Glaze.” His version of the figural lion, a repeated form for the Bell family, is believed to be the first produced and is speculated by Comstock to have drawn upon the signage for the Red Lion Tavern in Winchester, located a few blocks from the Winchester Bell Pottery location.

Pottery was always a necessary household commodity, and production remained strong until the Civil War. Although interrupted for a time by the conflict, production resumed again during the Reconstruction era and beyond. This period of pottery was dominated by the Bell family. The dynasty continued production as late as the 1930s through descendants of Samuel Bell. The Strasburg glaze formulas were recorded in a small black book, carefully guarded by the family to preserve the family glaze formulas. Gene Comstock related in a 1995 interview that the recipe book was still carefully guarded as late as 1976 even for direct Bell family descendants seeking the information for historical research.

Join us next time on February 18 to explore metalworking in the Valley!