The music for this installment is “Free America.”

Adapted from “Longrifles” by Timothy A. Hodges from the “Valley Pioneer Artists and Those Who Continue” exhibit catalogue and the “West of the Blue Ridge” text panels.

Life on the frontier spurred on the innovation and advancements necessary to create an accurate, economic, and efficient weapon different from those habitually used by the immigrants. German settlers brought a short, heavy rifle that had deep rifling grooves and a large bore. Though accurate, this “Jaeger” rifle was slow and difficult to load and required large amounts of scarce lead and gunpowder. The English, Scotch-Irish, and French immigrants brought a long, graceful fowling piece. Though light in weight and quick to load, the absence of rifling in the barrel severely limited its accuracy and range. It could be loaded with shot or, like the smooth-bore military musket, with a single lead ball; both consumed large amounts of lead and gunpowder.

Frontiersmen needed a lightweight, accurate firearm which was quick and easy to load and consumed small amounts of gunpowder and lead. By combining the desirable qualities of the jaeger and fowler with new innovations, the gunsmiths satisfied these needs. Reducing the depth of rifling grooves and using a greased patch around the ball made loading quick and easy without compromising accuracy. Reducing the size of the bore saved lead and gunpowder. Lengthening the barrel increased its range and gave it a graceful appearance.

The term “Kentucky rifle” is used to describe the American rifle developed in the eighteenth century by gunsmiths working on the Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and Carolina frontier. It served colonial settlers for protection, procuring food, and was used as a military weapon in the French and Indian War, the Revolutionary War, and the War of 1812.

By the 1750s, the American longrifle had evolved to the point where few mechanical improvements could be made. The number of gunsmiths increased greatly during the Revolutionary War. Gunsmiths took on extra apprentices and journeymen and allied tradesmen reverted to gunsmithing to meet the demand. After the Revolution, however, the demand decreased. A more effective rifle could not be made, and so smiths turned their skills decorative enhancements.

The post-Revolutionary War period to the 1820s was the “Golden Age” of riflemaking. The gunsmiths focused attention on decorating their rifles in the American rococo style. Regional design characteristics became more prevalent during this period with identifiable schools and patterns of influence.

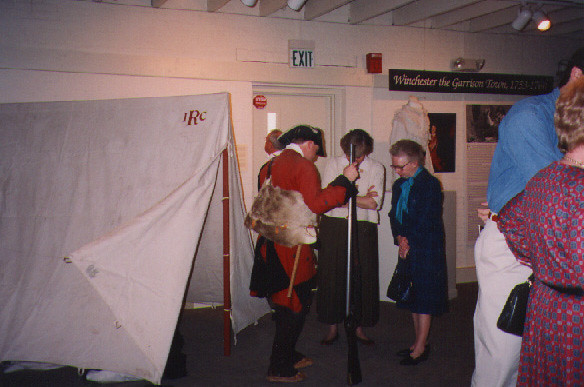

“[Winchester] is the place of general rendezvous of the Virginian troops, which is the reason of its late rapid increase , and present flourishing condition.” – Andrew Burnaby, 1775

Frederick County nurtured many gunsmiths because Winchester was the headquarters for militia activity during the French and Indian War. Winchester could boast of Adam Haymaker and Simon Lauck, two skilled craftsmen who trained apprentices who later worked in the Valley making fine guns. The “Winchester School” of rifle was carried west through Hampshire County and south through the Valley during the golden age of the Kentucky rifle.

Adam Haymaker is considered the “Father of the Winchester School” of rifles. He was working prior to the French and Indian War, and continued until his death in 1806. In addition to his son John, many other apprentices of Adam Haymaker helped spread his techniques and decorative details. His home and shop were located at 213 South Cameron Street.

Simon Lauck left Winchester with Daniel Morgan’s Riflemen in 1775, at the age of fifteen. He returned to Winchester in 1794, after a time as a gunsmith in Lebanon Township, PA. The log house at 311 South Loudoun Street was probably his primary residence. His rifles are stylistically similar to Adam Haymaker’s, but it is uncertain what association they may have had. Through the many apprentices he trained, Lauck transmitted the decorative elements characteristic of his style, including the four-petal flower patchbox and silver inlay acorn motifs. His apprentices include his sons Simon Jr., John, Jacob, and William, as well as Jacob Funk of Strasburg.

By 1830, a rapidly expanding population, westward migration, and the beginning of the industrial era brought the golden age to an end. The demand for rifles could only be met by factories which had little concern for art.

Join us next time on January 21 to explore early pottery in the Shenandoah Valley!