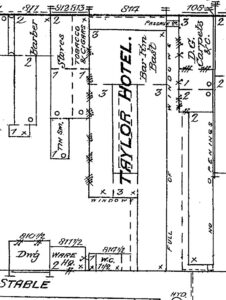

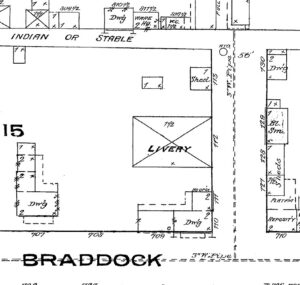

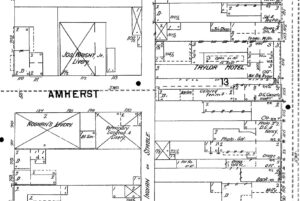

While the front facade of the Taylor Hotel was rehabilitated and now appears much as it did one hundred years ago, a sizeable area in the middle of the lot is now home to the Taylor Pavilion. The next time you visit this space downtown, take a moment to think on the now vanished part of this building and its opulent past.

Originally the “missing middle” was part of the hotel, with two wings connected by a hyphen with a courtyard between them. After the Civil War, the Taylor fell somewhat from its resplendent past, eventually being closed and converted to a McCrory’s around 1921. What could have been quite a dramatic fall from grace instead allowed for a rehabilitation of the upper floors, re-imagining the space into a theater.

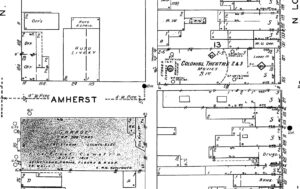

The Colonial Theatre, numbered 129 N. Loudoun St., was built not only for motion picture screening, but also to accommodate plays, musical acts, talent shows, and as a meeting place for organizations and speakers.

This adaptive reuse took some time as expected, but the work was completed in December of 1923, with the grand opening being held on Christmas Day. A. R. Roberts of New York was the supervising engineer. All of the electrical work and supplies were provided by the Butler Electric Company, while the furniture, rugs, and many interior decorations were furnished by P. C. Neidemeyer & Company.

Charles W. Boyer was the manager and lessee of the theater; Claire Dotterer was the resident manager, and Madelyn Hall was named musical director. Miss Dotterer subsequently hired three “usherettes” to assist patrons with finding their seats and providing programs.

Some of the innovations also included the attention to safety of the patrons. The opening description of the building stated, “Every precaution possible has been adopted to make the Colonial absolutely safe both from fire and panic.” The theater had “eleven exits, each of which is clearly defined in large glowing red letters” so that the “entire theatre could be emptied within five minutes.” Modern fire escapes with electrical lights were installed, fire hoses and chemical extinguishers were on hand, and the stage and the dressing rooms were equipped with an automatic sprinkler system.

We are very fortunate that a full description of the interior at opening was documented in the Daily Independent on December 24, 1923. We will be pulling heavily from this account to describe the Colonial Theatre. Be sure to click the links to visit the Stewart Bell Archives images of the associated descriptions!

“The main entrance of the New Colonial is situated on Main street, immediately north of the entrance to the J. G. McCrory Five and Ten-Cent Stores. A ticket booth is in front of the entrance, on the street, and in the foyer to the right there is a box office for use when road shows are presented.”

“The foyer and lobby and stairway of the New Colonial are imposing in appearance and beautifully decorated and lighted. The side walls and panels have been done in pink and ivory, the wainscoting and panel edges and columns in buff, while the stairway railings are of mahogany and the wooden panelling and interior woodwork is finished in mahogany.

“At the right of the stairway there is a large room which is to be used as a ladies’ lounge and which faces the main entrance on the right. Here a reading room for tired shoppers, whether they be patrons of the theatre or not, has been provided. Upholstered wicker furniture has been installed and the current magazines and newspapers and writing material will always be at the disposal of the public. A restful and comfortable atmosphere pervades the ladies’ lounge. The floor is covered with a velvet rug of old gold and rose.

“Up and down both sides of a wide stairway, which is divided by a mahogany railing, there is rubber matting, and the same material has also been placed on the landing floor above. At the left of the landing are the ladies’ and men’s retiring rooms and the men’s smoking room, while the balcony of the theatre is reached by entrances at both right and left of the landing.”

“Including the balcony and six boxes, it has a seating capacity of one thousand. There is a wide aisle down the middle of the theatre, reaching from the entrance doors to the orchestra pit, with aisles on either side of the immense room.

“The balcony upon which the picture machine is placed extends some distance from the main doors towards the stage. The distance between the picture booth on the balcony and the screen is 110 feet, and the distance from the back of the stage to the orchestra wall is 140 feet, while the theatre itself is 50 feet in width.

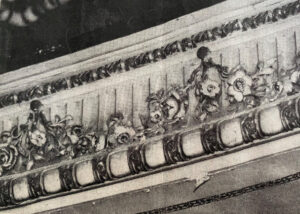

“The ceiling is white, decorated in gold and ivory, and the walls are finished in buff and ivory and polychrome.”

“The stage itself is unusually large for a moving picture theatre in a city the size of Winchester, and measures 21 feet, 11 inches from one end of the footlights to the other, and 19 1-2 feet, 12 inches from the footlights to the top of the proscenium arch. When road shows are presented, forty-two sets of lines have been installed to move the scenery and equipment, which is to be of the most modern type.

“The lighting system, both for the stage and for the theatre, is controlled from an electrician’s box which is located back of the curtain, on the left, 12 feet above the stage. The lighting control consists of a dead front switchboard and all interior theatre lighting is both indirect and direct. All the orchestra lights are controlled through dimmers, and this method also prevails with the stage equipment. Throughout the theatre itself both the direct and indirect systems of lighting are used, the suspended ceiling lights being softened by amber shades and the side lights with amber parchment shades.”

The Colonial also had a summer lighting and decor change. In the Daily Independent, 11 June 1924 the writer noted: “The stage has been completely redecorated, the heavy, winter velvet draperies have been replaced by light, cool, airy ones of silk and silver tone cloth. The house lighting has been changed to a delightful blue replacing the amber lights, while on the stage there is absolutely no bright light. The white lights have all been replaced by magenta and blue lights.”

Although we are not completely sure, it appears Charles Boyer retired from operating theaters in 1930.[1] Another story noted in 1926 Marshall Baker took over operation of the Colonial, implying Boyer gave up his Winchester enterprise before his Hagerstown theater. Warner Bros. purchased the theater in 1930 and appear to have been the last owners. The Colonial celebrated a change in showing schedule and admission prices to bring them in line with Warner Bros. policy on December 7, 1931 with a “gala reopening.”

Information on the theatre through its 1930s era is sparse. It is commonly repeated the theatre closed in 1939, which appears to be when the McCrory’s store was altered. A longtime McCrory employee, Betty Kline, relayed the 1939 date to the Winchester Star during an interview on the theater’s history July 12, 1986. It seems likely the theater seating was removed around 1939 to create a store room for McCrory’s, but according to Kline’s memory, the stage lights were still in place when she started in 1941.

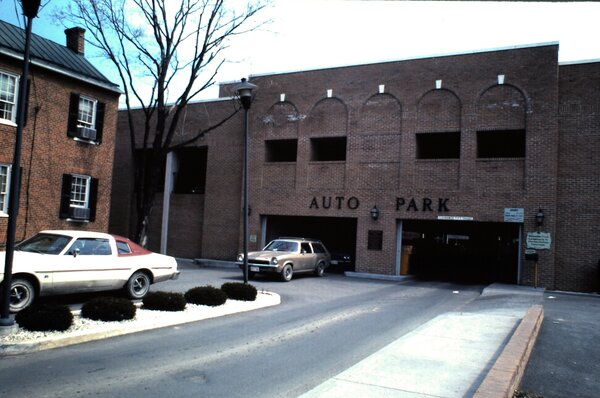

Dreams of restoring the theater to specialty film showings or conversion to IMAX were floated in the 1990s and 2000s with other downtown renovations. Unfortunately, the long-deferred dream was not to be. After close to a week of heavy rainfall in October 2007, the neglected roof drainage system over the theater collapsed under the weight of the water.

Salvaging the theatre was now impossible. In its stead, the removed central portion is now known as the Taylor Pavilion. Sections of the old limestone footers and foundation walls help make a tiered seating area. A small concrete stage area was installed as a nod to the space’s history. PHW was fortunate enough to host our 50th anniversary party there as the first major event in September 2014. The pavilion and event space is a fitting way to honor this once grand theater of Winchester’s past. The next time you are downtown, stop by the pavilion and stand in the pocket park. You just might be able to envision the glittering beauty and pageantry that graced the screen and stage here one hundred years ago.

Certain articles referenced in the creation of this blog post are not freely available online for citation but are held in the collection of the PHW Architectural Inventory.