Although PHW has secured lines of credit and several grants and loans through the National Trust as part of the Jennings Revolving Fund and Simon Lauck House project, there was always a need to replenish the coffers with fundraisers. Thus the Holiday House Tour was born in 1975.

Although PHW has secured lines of credit and several grants and loans through the National Trust as part of the Jennings Revolving Fund and Simon Lauck House project, there was always a need to replenish the coffers with fundraisers. Thus the Holiday House Tour was born in 1975.

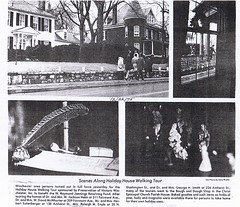

The tour took its cues from similar events in Charleston and Savannah. Grand homes would be traditionally decorated and opened to visitors via guided tours, with the proceeds from the ticket sales benefiting the local revolving fund. The first tour, fittingly enough, focused on the homes of PHW members along Fairmont Avenue, Amherst Street, and North Washington Street with a rest stop with hot drinks at Christ Episcopal Church. The Bough and Dough Shop was also held at the church.(1)(2)

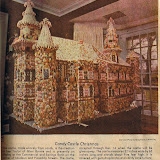

The formula proved successful, and the tour has been followed that pattern since then with only two noteworthy experiments in approach. The first, in 1978, was an “exterior only” tour of other in-progress Revolving Fund Houses on South Loudoun Street, with Lee Taylor donating an enormous gingerbread castle for a raffle. Although still a successful fundraiser, the event was quickly refocused on providing interior tours. The second change occurred in 1989, when Saturday tour hours were added for the first time, likely to help ease the difficulty of visiting the sites as the tour focused on county properties that year (not a “walkable” tour as is generally the norm). Since then, the Saturday hours morphed into the Preview Party on Saturday evening.

The formula proved successful, and the tour has been followed that pattern since then with only two noteworthy experiments in approach. The first, in 1978, was an “exterior only” tour of other in-progress Revolving Fund Houses on South Loudoun Street, with Lee Taylor donating an enormous gingerbread castle for a raffle. Although still a successful fundraiser, the event was quickly refocused on providing interior tours. The second change occurred in 1989, when Saturday tour hours were added for the first time, likely to help ease the difficulty of visiting the sites as the tour focused on county properties that year (not a “walkable” tour as is generally the norm). Since then, the Saturday hours morphed into the Preview Party on Saturday evening.

The tour, in addition to being a fundraiser, was also conceived by the organizers as a way to involve all of the members of PHW in an event. Although it is unlikely we have ever reached the goal of “100% participation” from our members, the tour regularly involves at least one-third of the membership in some capacity, whether as a homeowner, decorator, docent, musician, craftsman, baker, or ticket taker. Not too shabby.

|

| Holiday House Tours |

Images from some early Holiday House Tours have been scanned, with more waiting to be digitized. Take a trip down memory lane at the Picasa album.