PHW brings you two new (old) sets of photos and slides today. First is what appears to be images from the opening day reception for the Traditional Cabinetmaker exhibit held in the Kurtz Cultural Center in 1993. There are also a few images of the related programming activities, such as a lecture and appraisals. View Traditional Cabinetmaker Exhibit and Programs on Flickr.

PHW brings you two new (old) sets of photos and slides today. First is what appears to be images from the opening day reception for the Traditional Cabinetmaker exhibit held in the Kurtz Cultural Center in 1993. There are also a few images of the related programming activities, such as a lecture and appraisals. View Traditional Cabinetmaker Exhibit and Programs on Flickr.

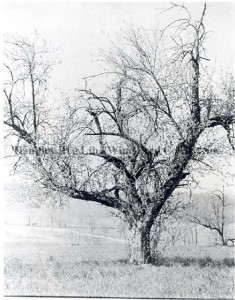

Also this week, we bring you a collection of slides of Town Run, walking from the Cork Street bridge, following Kent Street to Pall Mall, then past Hollingsworth Dr. to the Shawnee Springs area and Wilkins Lake. The slides are dated July of 1983, and the information written on the slides about the location of the photos (if available) has been transcribed. Virtual tour of Town Run in 1983 on Flickr