Welcome to the first installment of a weekly series on the history of Preservation of Historic Winchester to celebrate our 50th anniversary in 2014. Be sure to visit the PHW blog each Friday for the next installment.

Welcome to the first installment of a weekly series on the history of Preservation of Historic Winchester to celebrate our 50th anniversary in 2014. Be sure to visit the PHW blog each Friday for the next installment.

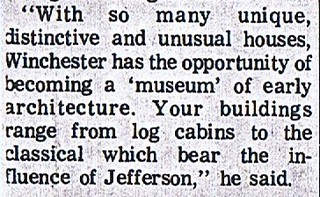

Winchester is a remarkable town for its abundance of historically significant architecture in a relatively small area, highlighting building styles from the late Colonial period to the modern day. The styles are modest for the most part, vernacular adaptations of the high-end construction found in larger cities, though that makes them no less valuable an historic asset. Winchester has been compared architecturally more than once to our southern neighbor Williamsburg, Virginia; however, we have a clear advantage in that much of our building stock has survived and did not require reconstruction to showcase the town’s charms and history. (1) (2)

This evolution from Winchester as a rough frontier town to a modern city is easily sensed through our buildings and often commented on with delight by tourists visiting Winchester for the first time. More than one visitor who has stopped in the PHW office has commented with evident enthusiasm, “You have so many old buildings downtown!” But this sense of wonder and value in our historic buildings – and by extension the very history of the city – has only come to be thanks to the untold hours of effort by advocates for historic preservation over the last fifty years.

This evolution from Winchester as a rough frontier town to a modern city is easily sensed through our buildings and often commented on with delight by tourists visiting Winchester for the first time. More than one visitor who has stopped in the PHW office has commented with evident enthusiasm, “You have so many old buildings downtown!” But this sense of wonder and value in our historic buildings – and by extension the very history of the city – has only come to be thanks to the untold hours of effort by advocates for historic preservation over the last fifty years.

Historic preservation, or the field of study pertaining to the conservation, interpretation, and reuse of the historic built environment, has its roots in the United States with efforts to preserve sites of national significance in the early 1850s, like Mount Vernon. (3) But these early preservation efforts concentrated almost entirely on landmark properties with national significance, leaving humbler construction, like the majority of Winchester’s buildings, without a strong advocate for retention. There were, after all, so many other old buildings . . . and if a parking lot would work just as well in that location, what was the harm in a little demolition? This need for modernization reached a fever pitch in Winchester around the 1950s. Instead of adapting still useful older buildings to new uses, demolition to provide access and parking for cars was seen as de rigueur.

The hardest-hit street in Winchester is almost undoubtedly North Cameron Street. In the late 1940s through the 1970s, this area was seen as ripe for demolition to add parking lots and drive-through lanes to service the growing population of automobiles descending upon the commercial downtown. An astonishing and horrifying number of architecturally and historically significant properties were carelessly leveled to make way for parking lots or other “car friendly” drive-through services, including:

107-111 North Cameron St., Empire (later Capitol) Theatre (4)

115 North Cameron St., Miss Portia Baker House (5)

118 North Cameron St., Holliday/Robinson House

119 North Cameron St., Baker/Snider House (6)

120 North Cameron St.

121 North Cameron St., Bantz Residence

126 North Cameron St., Barton Residence/Lutheran Parsonage (7)

130 North Cameron St., Harry Miller Residence

133 North Cameron St., Scott Affleck House (8)

200 North Cameron St., The Colonial/Baker-Jolliffe House (9)

218 North Cameron St., Winchester Seed Company

225 North Cameron St., Hart Hotel/Graichen Glove Factory (10)

12 North Cameron St., Conrad House (11)

|

| Vanished Winchester |

The Conrad House was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Next week, we will learn more about this house and why its proposed destruction sparked the formation of Preservation of Historic Winchester.